Back To The Master Index Of Art

Greek Architecture

- Hippodamus of Miletos

- The Sanctuary of Delphi

- Sanctuary of Poseidon at Isthmia

- Sanctuary of Zeus at Nemea

- Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia

- The Temple of Aphaia on Aegina

- The Akropolis, Athens

- The temple of Athena Nike

- The Parthenon

- The Erechtheion

- The temple of Olympian Zeus

- Read Survey 1 ch05 by dworthdoty on Slideshare

Greek Terms

- Columns. Caryatids

- Doric

- Ionic

- Corithian

- Acanthus leaves

- Coiled flowers

- The temple of Olympian Zeus

- Ionic Entablature (Greeek)- columns supported entablatures

- Architrave,

- Frieze (with relief)

- Cornice

- Pediment (triangular) with relief

5. Architecture

In Greek architecture, columns supported entablature as shown below. A classical entablature(1) consisting of the three essential elements — architrave(4), frieze(3) and cornice(2)– is shown below.

Note the Greek Entablature shown below from which the Romans refined their architectural model.

————————————————————–

————————————————————–

Shown above is the architrave of the Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome. It is the lintel or beam that rests on the capitals of the columns. It is an architectural element in Classical architecture.

Entrablature in modern structure

Many churches that exist today still incorporate at the entrance the classical structure known as the entablature. Entablature is all that part of a classical temple above the capitals of the columns; includes the architrave, frieze, and cornice but not the roof.

In Greco-Roman Classical architecture, the middle of the three main divisions of an entablature(section resting on the capital). The frieze is above the architrave and below the cornice (in a position that could be quite difficult to view).

Right above the columns, there is a long rectangular area called frieze. Relief figures are put in this area. In Doric style, the frieze usually consists of alternate triglyphs (projecting rectangular blocks with three vertical channels), and metopes (spaces).

Above the frieze is a triangular structure — it is called cornice. Often small sculptures are put on the upper arms of cornice for decorative purposes.

Enclosed with the cornice is a triangular area called pediment. You might view pediment being framed by cornice. Pediment is a classical architectural element consisting of a triangular section as shown above.

The frieze is usually ornamented with relief figures. Friezes seen on Roman buildings are usually decorated with plant motifs. The frieze also often features religious icons depicted in base relief, a breathtaking feature.

Often the entire structure is termed as cornice. So you might hear like “The architectural cornice projects beyond the building, providing a definitive and pleasing crown to the building.”

You can see the same architecture in our Writers Building above. The Entablature is on the top of capitals of the columns — from a distance it looks like a huge triangular structure. The cornice is the triangular frame inside which is the red pediment area. The pediment contains the seal of the Indian Government. The frieze area — between the capital and the cornice — contains layered rectangles that project out as it meets the bottom of the cornice. It does not have much decorative elements.

And you can also see the body of the building has a similar architecture as the model below:

Ornament design element with central blank shield and curling tendrils of leaves within a delicate filigree frame on an orange background.

Ornament design element with central blank shield and curling tendrils of leaves within a delicate filigree frame on an orange background.

Pilasters And Columns

During Italian Renaissance, Pilasters were mainly used on the facades of the palaces and churches. For example, shown below is Palazzo Farnese. It has three stories with windows and other architectural elements but there is no vertical element.

Palazzo Farnese, Florence

Here is how pilasters are used to obtain blocks or vertical elements in the facade. White pilasters are used below to separate the facade into elements where each element includes four windows. Also notice that the pilasters run all the way from bottom to top.

Also note that pilasters are decorative elements that run along the wall. Columns on the other hand are separate elements that stand by themselves. Look at the Senate Building in Rome with pilasters separating the facade into separate vertical units:

Although primarily used outside, pilasters are used inside rooms also. Look below.

Here pilasters are used as ornamental thin columns on the walls, they were used in palaces and churches particularly from the Greek to the Renaissance.

A popular decorative treatment of the palazzo was rustication, in which a masonry wall is textured rather than smooth. This can entail leaving grooves in the joints between smooth blocks, using roughly dressed blocks, or using blocks that have been deliberately textured. The rustication of a palazzo is often differentiated between stories.

Donato Bramante

————————————————————–

Renaissance Architecture

Basilica di Sant’Andrea | Alberti | Mantova

In the facade, the square, arch, and circle dominate. The roundel (circular area) set in the pediment of the facade and again over its doors is repeated on the walls of the nave between the chapels and culminates with the great circular opening of the dome. The vast interior space composed of geometric volumes harks back to Roman examples such as the Pantheon.

————————————————————–

High Renaissance

Karlskirche (St. Charles’s Church) in Vienna – It’s a baroque church

The Theatine Church in Munich 1700. The church was built in Italian high-Baroque style.

St. Johann Nepomuk, better known as the Asam Church is a Baroque church in Munich

Drawing of a Jug by Holbein 1645

Some of the most architecturally-stunning buildings in the world are places of religious worship. Architectural cornice not only enhances the architectural design of these sacred locations, but also helps to protect these structures from the elements. Many churches that exist today still incorporate the classical structure known as the entablature. The frieze often features religious icons depicted in bas relief, a breathtaking feature, while the architectural cornice projects beyond the building, providing a definitive and pleasing crown to the building.

Pediment

In classical, neoclassical and baroque architecture, a pediment is the triangular gable that forms the end of a pitched roof.

An artist’s reconstruction, from the 19th century, of the appearance of the Parthenon in the late 5th century BCE. It shows the East side, with the pediment depicting the birth of Athena.

Freize

In interiors, a frieze in a room is a long stretch of painted, sculpted or even calligraphicdecoration. Sometimes it is in a position that is normally above eye-level. Frieze decorations may depict scenes in a sequence of discrete panels. The material of which the frieze is made of may be plasterwork, carved wood or other decorative medium.

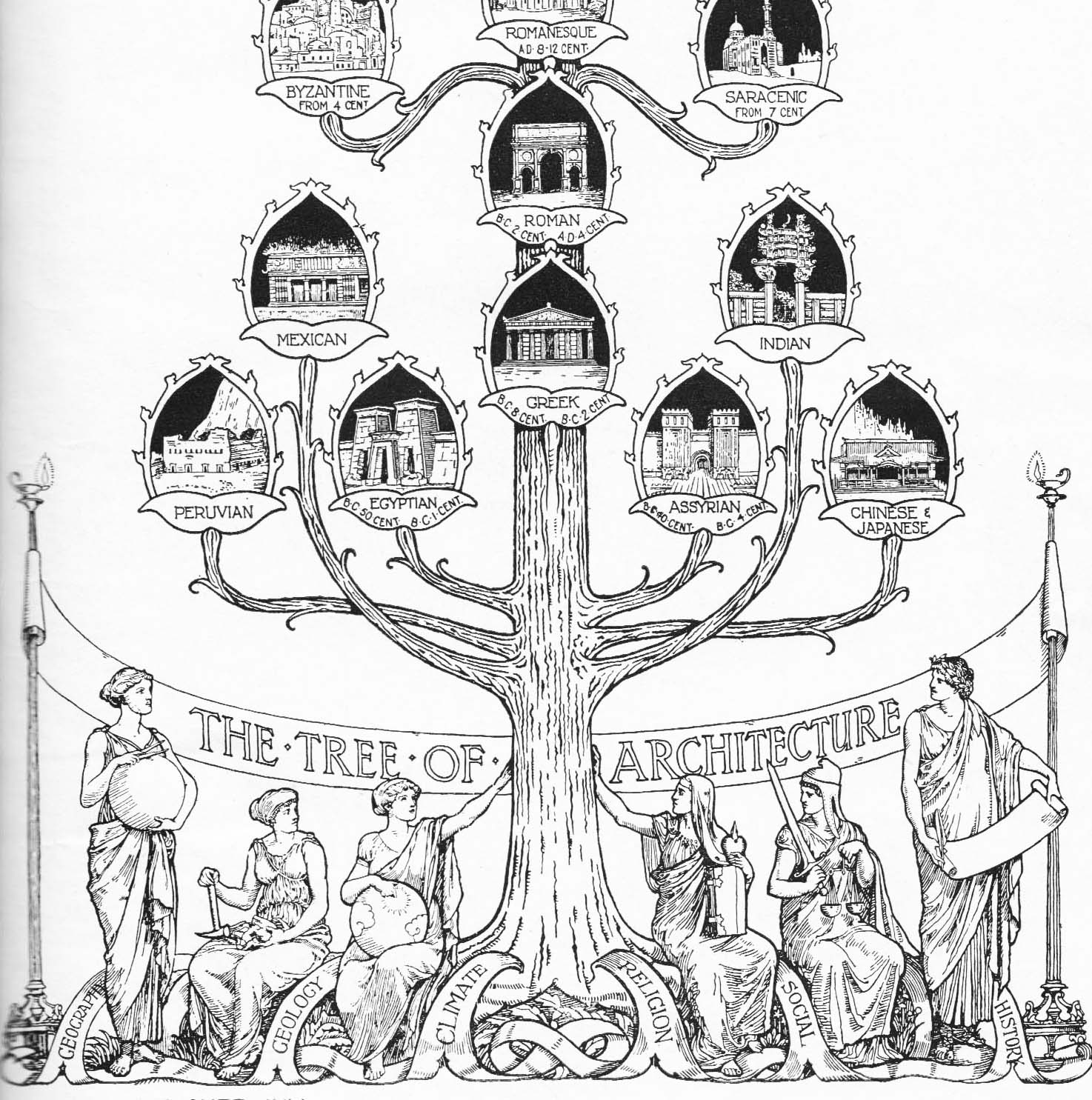

1. History Of Architecture

The above tree contains the architecture during the Classical period of Rome (0-400AD). After 400AD, Rome goes into oblivion during the Middle Ages (400-1200AD). The power and progress shifts to France, Spain, and other western parts of Europe.

After 1250, Renaissance starts in Florence and Rome. It becomes the seat of Christianity agaib under the papacy. The architects of Italy study the ruins of classical Rome and under the sponsorship of Popes, start reconstructing Rome again to regain the glory of its classical ages. That is known as the Renaissance Architecture.

1.1 Introduction to Classical Roman Architecture (0-400AD)

1. Roman Architecture: http://opencourseware.kfupm.edu.sa/colleges/ced/arc/arc110/files%5CLecture_Slides_Module_7_Roman.pdf

Map of ancient Rome

The above shows all the major parts of Rome.

All artefacts in the Forum.

The Colosium

1. Tempio di Cesare, Rome, Italy

Senate House of Julius, Rome

Temple of Vesta, Via dei Fori Imperiali, Roma

Basilica of Maxentius, Clivo di Venere Felice, Roma

Tabularium, Via di San Pietro in Carcere, Roma

Column of Phocas – Roman Forum, Via dei Fori Imperiali, Roma

Antoninus and Faustina Temple, Rome

Welcome to Roman Architecture.

I’m Professor Kleiner.

And what I’d like to do today, is to give you a sense of some of the great buildings, and some of the themes that we will be studying together this semester.

I think it’s important to note from the outset that Roman architecture is primarily an architecture of cities.The Romans structured,a man made worldwide empire out of architectural forms.And those architectural forms revolutionized the ancient world, and exerted a lasting influence on the architecture, and the architects of post classical times.

This semester we will be concerned, primarily with urban communities, with urban communities.And we will, in the first half of the semester,we will focus on the city of Rome,and in the second, a-,and, and also central Italy, including Pompeii.And I wanted to show you at the outset an aerial view of Rome,you see it over here on the left-hand side of the screen,that situates us in the very core of the ancient city.

You see the famous Colosseum. The very icon of Rome.

At the upper right. You see the Roman Forum as it looks today.And you see a, a part of the Capitoline Hill transformed by Michelangelo into the famous Piazza del Campidoglio,

as well as the Via dei Fori Imperiali of Mussolini, built by Mussolini. And the Imperial Fora.

So the city of Rome again we’ll be concentrating on at the beginning of this semester, as well as the city of Pompeii. An aerial view of Pompeii as it looks today.

You can see many of the buildings of the city.Including the houses and the shops and also the entertainment district.This is the theatre and the big music hall of ancient Pompeii,the amphitheater is over here. And you can see, of course, looming up in the background the Mount Vesuvius.The mountain that caused all that trouble in 79 AD.So that’s the first half of this semester.

The second half of this semester, we are going to be going out into the provinces,into the Roman provinces.And that is going to take us, and we’re going to look at the provinces both in the eastern and the western part of the empire, and that will take us to Roman Greece ,it will take us to, Asia Minor.Asia Minor, which,of course, is modern Turkey, it will take us to North Africa,it will take us to the Middle East.In what’s now Jordan and Syria and it will also take us to Europe,to western Europe.To cities like, to cities in France and to cities in Spain.

And let me just show you an example of some of the buildings that we’ll look at as we travel to the provinces.This is the library of Celsus. In Ephesus,on the western coast of Turkey.

This, the theater,a spectacularly well preserved theater at Sabratha you see in the upper right hand side.And down here a restored view of the masterful Palace of Diocletian,one of the late Roman Emperors,in a place called Split.Which is in Croatia along the fabulously gorgeous Dalmatian coast today.So those are just a sampling of the kinds of buildings that we’ll look at in the provinces.We’re going to be seeing we’ll be concentrating on the ways in which the Romans planned,and built their cities.And its important to note from the very outset that Rome itself grew in a very ad hoc way.

And we can tell that.

Here’s a Google Earth image showing that core of Rome with the Colosseum with the famous modern Victor Emmanuel Monument that looks either like a wedding cake or a typewriter. It’s very white and it’s, it’s called the wedding cake by a lot of the locals.

You see that here, but it’s a landmark in Rome.and, the Capitoline Hill with the Campidoglio over here,the forum, the Roman forum,the imperial forum, on, on this side.But you can see from the relatively crooked and narrow streets of the city of Rome as they look from above today,you can see that again, the city growing a fairly ad hoc way, as I mentioned. It wasn’t planned all at once.It just grew up over time,beginning in the eighth century B.C..Now this is interesting.Because what we know about the Romans is when they were left to

their own devices and they could build the city from scratch,they didn’t let it grow in an ad hoc way.They,they structured it in a,in a very care-,very methodical way.That was basically based on military strategy, military planning.

The Romans they couldn’t have conquered the world without obviously havinga masterful military enterprise.And they everywhere they went on their various campaigns,their various military campaigns.They would build, build camps and those camps were always laid out in a very geometric plan along a grid,usually square or rectangular.So, when we begin to see the Romans building their ideal Roman city,they turn to that so called castrum or military camp design.

And they’d build their cities that way.And Is how you here one example,we’re using Google Earth here, again,another example of, alright, a-,an example of a city, called Timgad,T-I-M-G-A-D, which is in modern Algeria,and the ancient city, still survives,and if we look at this Google.Earth image of it.You can see, there’s no later accretions as we have in Rome.

No later civilizations built on top of it.You can see the ideal Roman plan,which as I’ve said is usually either a square or a rectangle.It has in the center,the two main streets of the city.

The north south street is called the cardo,C-A-R-D-O, the east-west street is called the decumanus, D-E-C-U-M-A-N-U-S, we’llgoback to all of this in the future, soyou don’t have to worry about it today.The cardo and the decumanus, and you can see that they cross exactly,they intersect exactly at the center.Of the city.And then the rest of the city is arraigned in blocks, very regular blocks.

This grid plan that I mentioned before,and then some of the major monuments,whether it’s the theatre or the forum.You know, are arraigned indifferent parts of the city.And then these blocks constitute essentially the housing and the shops and so on and so forth.This is a city that was planned in around 100 AD under the emperor Trajan.And again it gives us an inkling of what the Romans,when the Romans thought about ideal Roman town planning it was this grid plan.Not Rome, but this grid plan that they had very much in mind.Cities like Rome, like Timgad, and most of the others that we’ll look at in the course of this semester.Were surrounded by defensive walls,as a mass,as a major military machine in its own right,

Rome was only too aware of the dangers of, of attack from others,and consequently they walled their cities, and we will look at the two major walls in Rome, as well as walls of other parts of the Roman world, I promise not to spend too much time on walls.Because they are essentially piles of stone, but, but they’re,they’re important in their own right and I will speak to them on occasion.

And especially the two in Rome,you see them here.

This is the first wall,wall in Rome, the so called Servian Walls which was built in the Republic,in the Roman Republic, to, To, to, surround, the city.The republican city.Essentially, the Seven Hills,the famous of Seven Hills Rome.

To surround the Seven Hills of Rome in the fourth century,B.C. You see a section of it here.

This wall.Any of you who have come to Rome by train.In the Stazione TerminiSee a very extensive section of the Servian walls as you get out,I don’t know if you’ve noticed it,but you should see an extensive section of the Serbian walls right outside, the train station.This is a different section than I picture I took on the Aventine Hill.

Showing a part of that wall.And that was eventually replaced by later walls.

The city grew over time.It needed a, a, a,a more extensive broader wall system.And in the late 3rd century AD under the emperor Aurelian, the famous Aurelian Walls were built.

The Aurelian Walls as you know,there’s no way you’ve missed those.I’m sure if you’ve been in Rome,you’ve seen the Aurelian Walls.They’re there, they’re very much there.At least if you’ve left the city, maybe if you’ve just gone into the core of the cityand haven’t gone beyond that you might not have seen that if you left the city,you’ve seen the Aurelian walls the very impressive set of walls that it,encircled the latest city.

One thing that’s apparent to you as you look at these, even if you have no knowledge whatsoever of Roman architecture is these are made of very different kinds of materials. So technical issues come to the fore right away as one analyzes this sort of thing.

In the early period, essentially blocks of stone piled one on top of the other for the wall.Here a more sophisticated use later on in the empire of a new technology that we’re going to talk about a lot this semester, and that is concrete.And what concrete did to revolutionize Roman architecture.

Concrete, in this particular case, faced with brick.

https://class.coursera.org/romanarchitecture-002/wiki/syllabus