Back to Alexander The Great

Back to The History of India

Map of Macedon to India during Alexander

This post has been taken out of Chapter LIII titled Camp on the Hydaspes from “A History of Greece” by Connop Thirlwall.

- Alexander PDF

- Alexander’s empire and his route

- Map of conquests of Alexander

- Map 2

- Map 3

- Alexander The Great- Conquest Of India Video (Minutes 12:20, 18:30, 27:10, 28:37, 43:20)

-

Alexander the Great: Mallian Campaign 326 BC

- https://legioilynx.com/2018/10/01/alexander-and-his-conquest-of-india/

- https://www.slideshare.net/jackhennessygarrity/alexander-the-great-51169434

- https://defence.pk/pdf/threads/battle-report-13-battle-of-jhelum-hydaspes-326-bc.299912/page-3

- The marriage of Stateira II to Alexander

- The Anabasis of Alexander

Modern day map of Alexander’s route

Major milestones during his India campaign

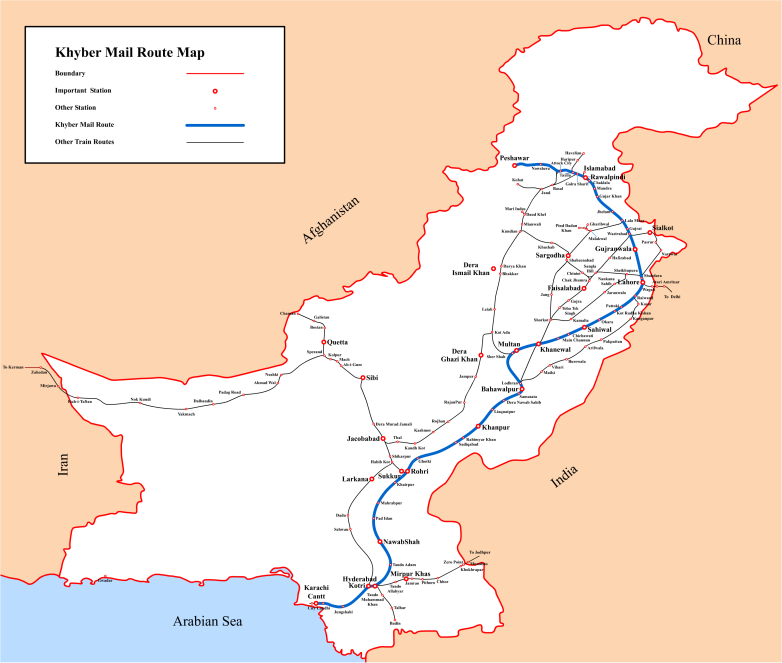

Alexander’s route: Map showing current day Kabul – Khyber Pass – Peshawar – Taxila – Islamabad. Alexander came through this route.

| Crossing of Indus river | Early spring 326 |

| In Taxila | April 326 |

| Crossing of Hydaspes (Jhelum) river and battle with Puru | May 326 |

| Five rivers campaign | June and July 326 |

| At Hyphasis (Beas) river | End July 326 |

| Back to Hydaspes | Aug 326 |

| Start down Indus river | Oct 326 |

| Mallian Campaign | Nov and Dec 326 |

| Campaign on lower Indus | Jan to June 325 |

| In Patala | July 325 |

| Exploration of delta on Indus | Aug 325 |

| Oritian Campaign | Sep 325 |

| Crossing desert of Gedrosia (Baluchistan) | Oct and Nov 325 |

Spring 326 BC: King Taxiles of Taxila surrenders to Alexander without fight

During spring of 326 BC, Alexander crossed the Indus near Attock (near Islamabad) and enters ancient Taxila, whose ruler, Taxiles (or Ambhi), furnishes 130 war elephants and troops in return for aid against his rival Porus, who rules the lands between the Hydaspes (modern Jhelum River) and the Acesines (modern Chenab River). Attock is of both political and commercial importance, as this is about 120 KM east of Khyber Pass. After crossing the Khyber Pass, Alexander the Great, Timur and Nader Shah crossed the Indus at or about Attock in their respective invasions of India.

The truly decisive arm of Alexander was the Companion Cavalry. In battle, it would form part of a hammer and anvil tactic: the Companion cavalry would be used as a hammer, in conjunction with the Macedonian phalanx-based infantry in the middle, which acted as their anvil. The phalanx would pin the enemy in place, while the Companion cavalry would attack the enemy on the flank or from behind.

In all of Alexander’s major battles, Coenus commanded the right-most battalion of infantry in the massive Macedonian phalanx. In the Macedonian battle tradition, the most favoured soldiers were positioned on the right. In this regard, Coenus’s distinction as commander of the “best” infantry of the phalanx indicates he was tactically reliable, probably extremely intelligent in warfare, and brave in battle; he was probably the epitome of the highly respected “lead-by-example” Macedonian general.

The Companion Cavalry were made up of highly-trained landed nobility. The Companions were divided into 8 squadrons of 200 men – each from a particular province of Macedon – with the exception of the Royal Squadron, the hand-picked bodyguards which totaled 400 men. Companion cavalry would ride the best horses, and receive the best weaponry available. In Alexander’s day, each carried a xyston, a 12-13 foot long spear, and wore a bronze breastplate, shoulder guards and Boeotian helmets, but bore no shield. A kopis (a curved slashing sword) was also carried for close combat, should the xyston break. Their horses had a large amount of thick felt draped over their sides, while they probably had partial breast and head plating for protection against spears, missiles and the like. The Companions main function was to charge selected opponents or exposed flanks of enemy unit, most usually after driving the enemy horse they engaged from the field. They were always positioned on the right wing, considered the position of greatest honor.

[NOTE: Hypaspists, labeled above as “elite heavy cavalry,” were actually elite heavy infantry]

The next most elite unit – stationed next to the Companions – was the Hypaspists, heavy infantrymen equipped and armored like the classic hoplites. Their main job was to guard the right flank of the phalanx. The Hypaspists were also from higher-class families (similar to the Companions). In addition, they were used for special battlefield missions with the Agrianians (who were elite javelinmen or peltasts) and light cavalry wearing linen or leather armor and carrying swords or even xyston.

Battle of Hydaspes (Jhelam) (Video Alexander the Great: Battle of the Hydaspes 326 BC)

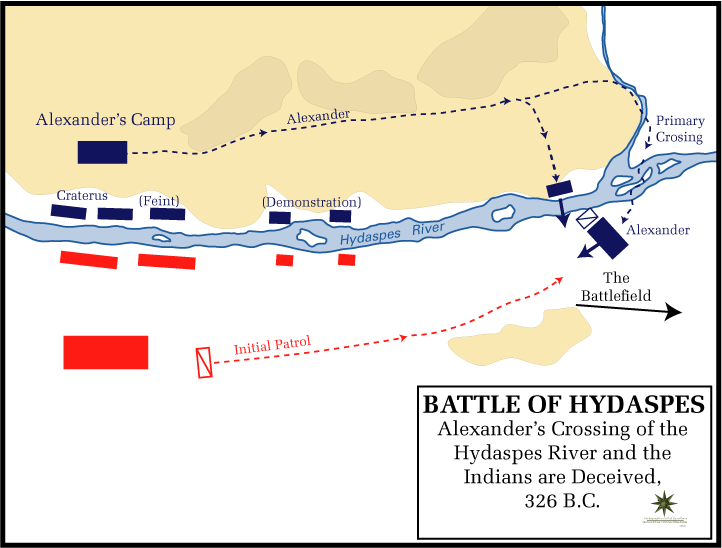

Alexander’s crossing of the Hydaspes River.

Porus enjoyed the advantages most armies enjoy when defending their own territory. For example, he had a short supply line and could hold his defensive position indefinitely. He intended to carefully guard the best possible river crossings and eliminate each wave of Alexander’s army as it came ashore.

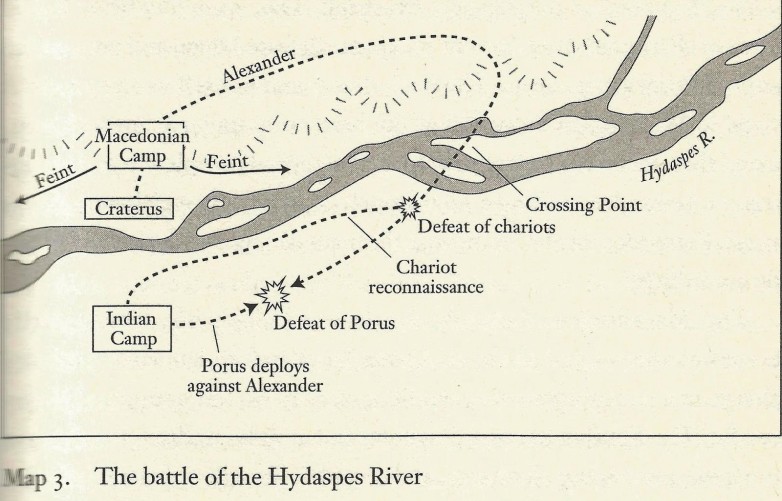

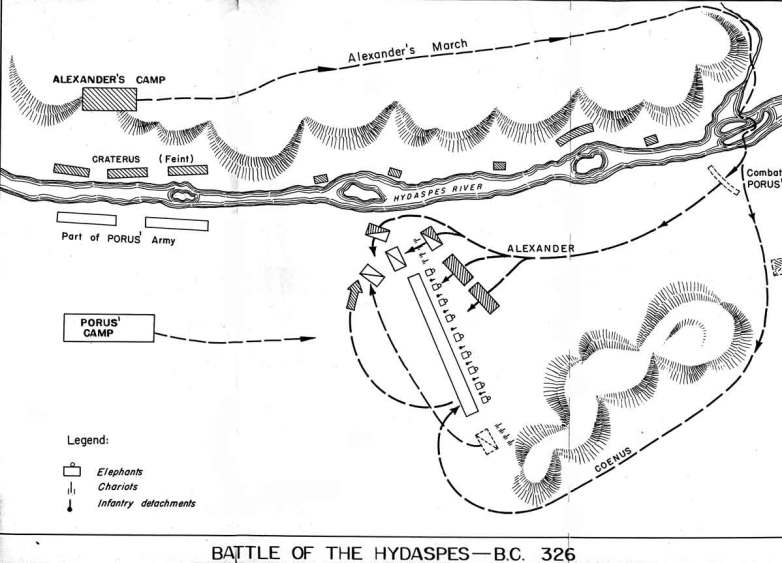

To deceive his opponent, Alexander built numerous campfires along his side of the river, marching his men back and forth in formation; meanwhile, his scouts searched for the best possible crossing spot. “Alexander’s answer was by continual movement of his own troops to keep Porus guessing: he split his force into a number of detachments, moving some of them under his own command hither and thither all over the place, destroying enemy possessions and looking for places where the river might be crossed,” wrote Arrian. Porus’s forces stationed on the west bank of the Hydaspes initially shadowed each movement of the enemy on the opposite bank, but after a while they stopped. Porus eventually came to believe that all of the marching was nothing more than a diversion designed to confuse him.

After a long and tedious search, Alexander’s scouts found a suitable crossing 18 miles upstream from the Macedonian camp at a heavily wooded bend in the river. Alexander believed it would offer good cover for his troops. To keep Porus unaware of his crossing, Alexander left General Craterus in the camp opposite Porus’s position. Alexander instructed Craterus to wait until the battle was underway to lead his reserve troops across the river.

Alexander crossing the river (From page 19)

The king himself, with Ptolemy, Perdiccas, Lysimachus, and Seleucus, the founder of the Syrian dynasty, went on board a small galley, with a part of the hypaspists. The woody island concealed their movements, until, having passed it, they were within a short distance of the left bank. Then first they were perceived by the Indians stationed there; who immediately rode off at full speed to carry the tidings to their camp.

The Macedonians arrived at the intended crossing during a heavy thunderstorm. The river could not be forded because of its depth, so Alexander ordered his men to construct rafts made from their tents. Alexander also ordered his engineers to haul as many as 30 boats used by his army to cross the Indus to the Hydaspes crossing. Alexander’s main force was composed of heavy cavalry, mounted archers, and various infantry units. Arrian says he had 6,000 foot soldiers and 5,000 horsemen. The troops cast off from the east bank under cover of darkness. The crossing did not go smoothly. Instead of reaching the opposite shore, the Macedonian soldiers landed on a large island located in the middle of the river. From the island to the opposite bank, the Macedonian soldiers had to swim since the channel between the island and the opposite shore was too narrow for the boats and rafts.

After reaching the opposite shore at dawn, Alexander regrouped his forces and put them in battle order. Some of his infantry units had not yet arrived, but Alexander advanced all the same. A defensive screen of Asiatic mounted archers, which included the famous Scythian archers, was placed in front of the advancing army to protect it.

Alexander goes 17 miles east from his main camp shown on the left of the map. Then, on one night he decides to cross the river Jhelum. He divides his army in 2 parts. He asks 12000 to stay at the bank of Jhelum as shown, and, marches with 18000 to cross the river with him leading the way. Then in that stormy night, after much effort, he crosses river.

Puru’s men notice them in the morning and informs Puru. Puru has now a dilemma that Alexander astutely created: He has General Creterus’ army right across from him (Alexander did this to pin Porus down here). Should he move right to meet Alexander?

He has no idea how big Alexander’s army is. If he moves right, then the unit across him will cross the river and attack his from the rear end and his force will be sandwiched.

Puru thinks the army opposite him is the main force and the force Alexander is carrying is relatively minor. So he stays put and sends his son to meet Alexander.

He sent a picked force of 3,000 cavalrymen and 120 chariots against the Macedonians led by his son. The Indian vanguard fought with great courage, but it was no match for Alexander’s heavy cavalry. Porus’s son was slain in the initial clash.

But due to heavy rain, the battlefield — shown with a dark rectangle — is now a mud pit and the chariots become sitting ducks as they cannot move. So, Alexander defeats Puru’s son. His son is killed. The surviving soldiers report to Puru that Alexander is coming with the main force and that Puru’s son is dead.

Next, Alexander led his army toward the Indian camp. After six miles, he halted to wait for the rest of his infantry to arrive. Alexander army was exhausted, and he chose paused to give his men some rest before launching the main attack.

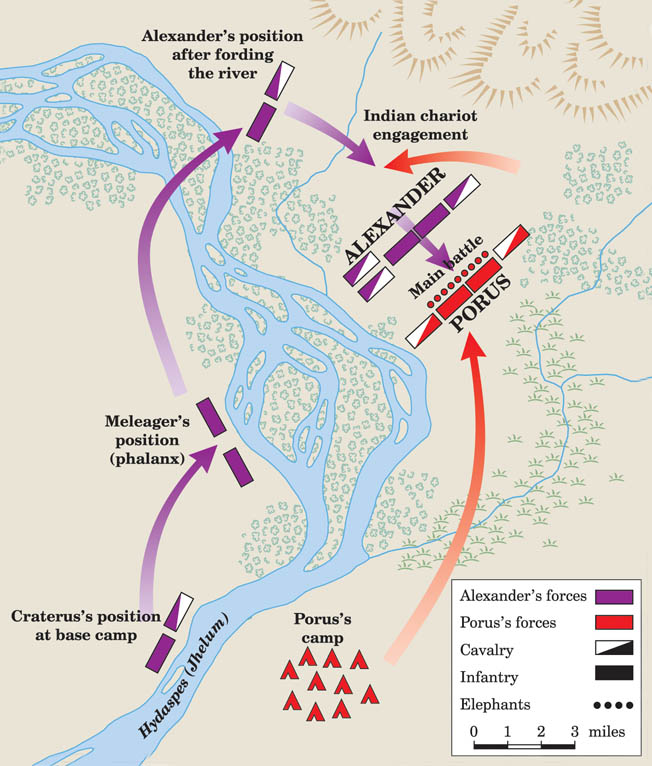

Meanwhile, Porus deployed his main force for battle. He had approximately 20,000 cavalry, 4,000 light cavalry, and 200 war elephants. Porus did not mass his elephants together but instead placed them at regular intervals. His light cavalry was stationed on both flanks behind a screen of six-man chariots. The Pauravan infantry phalanxes, which were not as well trained or strong as the Macedonian phalanx, were placed not only behind the elephants but also between them. Porus took his position in the center of the line mounted on his elephant.

The game for Alexander is now how to fight this battle that is not an infantry battle?

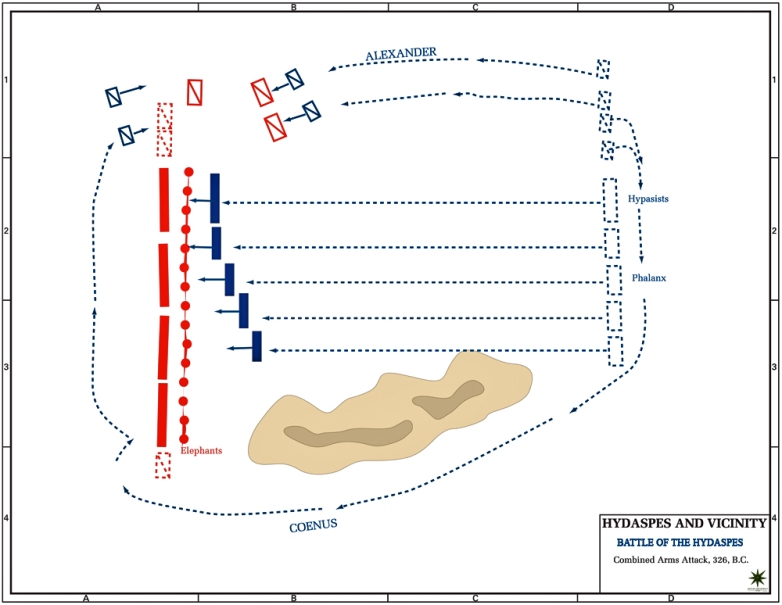

Alexander deploys his elite guard of 4000 cavalry towards Puru’s left flank. Puru only has 2000 cavalry, a 1000 on each wing. So, he led his armored Companion Calvary (his elite guard) to attack their left wing.

Porus, seeing the mismatch, decides to pull his 1000 cavalry from the right flank and reinforce the left. And that’s precisely what Alexander has been waiting for!

Now Alexander makes his brilliant move. He orders Conus, one of his commanders to move 2000 cavalry away from Puru’s left flank and attack the defenceless right flank. The 2000 cavalry now moves freely from the right and attacks Puru from behind. Puru is sandwiched now with no place to escape.

It was a completely different story on the Indians’ left flank, though. Alexander led his heavy cavalry in a spirited charge that drove back his adversaries. The effect of the Macedonian cavalry attack precipitated a crisis for Porus’s left wing. To face the emergency, Porus sent part of his cavalry from the right to circle back and help the left wing against Alexander.

Shortly afterward, Porus ordered a general advance of his elephants against the Macedonian phalanxes. The elephants, which were organized into a separate corps, were used as shock troops. They were frequently used during the period against enemy cavalry because horses had a terrible fear of the animals and recoiled at their strong smell. But Porus’s elephants were not facing cavalry but rather a compact mass of heavy infantry. The psychological effect of the encounter on the Macedonian pikemen was unknown because it was the first time they had encountered elephants in battle. Likewise, Porus had no idea how his elephants would stand up to disciplined infantry.

The elephants charged into the Macedonian ranks, trampling the soldiers in their path. The Macedonians seemed on the point of breaking after the initial charge of the elephants. But the veteran infantrymen, who had faced all manner of enemies in their long trek from Macedon to India, began almost immediately to reorganize themselves. They gradually pulled back without breaking their ranks. Meanwhile, Alexander’s Asiatic horsemen harried the elephants from the flank, closely cooperating with the specially trained light infantry that stabbed the ele- phants’ legs.

Over time, the wounds Alexander’s tenacious foot soldiers inflicted on the elephants caused them to turn around and head for the rear. But the Macedonian cavalry had by then swung behind Porus’s army. The momentum then turned in Alexander’s favor. The Macedonian phalanxes had switched to the attack. Porus’s poorly disciplined infantry could not stand up to their Macedonian counterparts.

Porus’s elephants tired quickly, and their charges against the Macedonian infantry grew feeble as time passed. The elephants, maddened by the harassing attacks against their flanks and legs, then began to rampage through the dense ranks of Indian infantry as they sought to escape. This caused more damage to the Indian infantry than was inflicted by the enemy. It was not long before great gaps had been opened in the Indian infantry to be exploited by the Macedonians. Alexander’s phalanxes smashed into the lightly equipped Indian infantrymen, who were no match for them. Porus’s army by then was in complete disarray.

Coenus moved quickly to exploit the situation. He led a contingent of cavalry against the horsemen on the extreme right of Porus’s army. After driving them off, he also swept into the Indian rear to complete the envelopment of Porus’s hapless army. Porus’s left flank, which already had been routed by Alexander’s charge, was struck from behind both by Alexander’s horse and those led by Coenus. The only escape route left for Porus’s troops was to try to cross the Hydaspes. But Craterus brought Alexander’s reserve across the river, arriving on the battlefield at a crucial moment and adding their additional weight to the Macedonians’ final attack. Porus remained on his elephant throughout the battle and witnessed the complete destruction of his army. He had fought hard and as a testament to his valor had suffered severe wounds. The proud king could not accept defeat, though, and he encouraged his men to fight on.

Alexander’s veterans and his allied soldiers had crushed Porus’s army. The Indian losses amounted to 12,000 killed, wounded, and missing, and 9,000 captured. In contrast, Alexander’s losses amounted to 1,000 men. One of the Macedonian casualties was Bucephalous, Alexander’s beloved horse, which died from wounds he suffered during the height of battle. It was a bittersweet moment for the great Macedonian king. As a special tribute to his beloved horse which had served him faithfully since his first adventures, Alexander founded the city of Alexandria Bucephalous on the west bank of the Hydaspes.

Surrender of Porus

Porus himself, mounted on an elephant, had both directed the movements of his forces, and gallantly taken part in the action. He had received a wound in his shoulder, yet, unlike Darius, as long as any of his troops kept their ground, he would not retire from the field. When, however, he saw all dispersed, he too turned his elephant for flight. He was a conspicuous object to Alexander’s army, and easily overtaken.

Alexander, who had observed and admired the courage Porus had shown in the battle was desirous of saving his life. He sent Taxiles to summon him to surrender. But since Taxiles was an old enemy of Porus, he could not gain a hearing for Alexander’s message.

Alexander nevertheless continued to send messengers after him ; and at length, hopeless of escape, and worn with fatigue and thirst, he yielded.

Porus then alighted from his elephant, and permitted himself to be led into the conqueror’s quarter. All he would ask of Alexander, was to be treated as a king. Alexander observed that this was no more than a king must do for his own sake.

Porus’s expectations could scarcely have equaled the conqueror’s munificence. Alexander not only reinstated his royal dignity, but also assigned a large addition of territory.

After victory of the Battle of the Jhelum (Hydaspes)

Alexander, after he had buried his slain and solemnised his victory with his usual magnificence, allowed the main body of his army a month’s rest, perhaps in the capital of Porus. The continuance of the rains was probably the chief motive for this delay. But before he quited the scene of his triumph, he founded two cities on both sides of the Hydaspes (Jhelum) river, one, which he named Nicaea, near the field of battle, the other near the place where he had crossed the river; this he named Bucephala, after his gallant steed, which had sunk either under fatigue or wounds in the hour of victory.

Alexander returning home

At last, the pragmatist in him won out and he decided to announce that the army would return home. The men surged around his tent, cheering, weeping and calling down blessings upon him for giving in to their wishes. It was the only defeat Alexander had ever suffered.

If the men thought they were about to embark on a peaceful march, they were mistaken. Alexander ordered a prompt return to the Hydaspes, where he commanded the building of a large fleet to descend the Indian rivers south to the sea. From its shore, the army would march home. But there was a rub. The army would have to conquer its way to the sea.

At last, the pragmatist in him won out. He seized upon bad omens to announce that the army would return home. The men surged around his tent, cheering, weeping and calling down blessings upon him for giving in to their wishes. It was the only defeat Alexander had ever suffered.

Alexander decides to sail down the Indus river system to the Ocean

Alexander the Great: Mallian Campaign 326 BC by BazBattles — Watch the video for Alexander’s route all the way back to Susa.

In 327 BC, Alexander married Roxana despite the strong opposition from all his companions and generals. Alexander thereafter made an expedition into India and while there he appointed Oxyartes as the governor of the Hindu Kush region which was adjoining India. During this period, Roxana was in a safe place in Susa. When Alexander was coming back from India, he, for this reason, returned to Susa.